Ionut is 37 years old and is addicted to heroin.

We met him in a drug consumption room in Lisbon, where he goes to use drugs in a controlled environment, with sterile syringes, under the supervision of specialized staff.

Ionut is 37 years old and is addicted to heroin.

We met him in a drug consumption room in Lisbon, where he goes to use drugs in a controlled environment, with sterile syringes, under the supervision of specialized staff.

"An addict is an ill person, not a criminal". Inside a consumption room in Portugal, the country that decriminalised drug use

English Section

11/01/2023

More than 20 years ago, Portugal became the first country in the world to fully decriminalise drug use. This allowed for the construction of a system where addiction was treated as a health problem, and drug use in general became a destigmatised subject, openly addressed in education and in the public space.

Contested or viewed skeptically by some, admired and applauded by others, the Portuguese model is ever-present in debates on illicit substance policy. To better understand how it works and how Portugal's approach fits into the European context, PressOne spoke to experts in the field, both in Portugal and at EU level.

Our reporter has also visited an NGO in Lisbon that works with addicts, in order to understand what drug harm reduction really means.

Ionuț is 37 years old and comes from Iași, Romania. His grandparents brought him up, he finished ten years of school and left the country when he was 23. Although he says he often wished to go back, he never did. Ionuț first came across drugs in Hamburg, Germany, almost ten years ago. Today Ionuț lives in Lisbon and is addicted to heroin.

- I've been everywhere. Paris, Berlin, London...

- And you never thought of going back home?

- Oh my... many, many times!

- So?

Mulți ne citesc, puțini ne susțin. Fără ajutorul tău, nu putem continua să scriem astfel de articole. Cu doar 5 euro pe lună ne poți ajuta mai mult decât crezi și poți face diferența chiar acum!

- I couldn't. These drugs... Are you going home for the holidays?

- Yes, I will.

- And what food are you gonna have?

- I don't know, whatever Grandma makes. Traditional, as it is for Christmas.

- Sarmale (n.r. Romanian traditional dish)? Oh, how I miss having those!

Predator in Robes: The Diocese of Iași and the Vatican Buried a Sexual Assault Committed by a Catholic Priest Against a Minor in Bacău, Failing to Alert Prosecutors

A Roman Catholic priest abused a 13-year-old girl in the parish where he served in Bacău County: the bishop of Iași knew about it, sent the case to the Vatican, and applied canonical sanctions, but did not notify the authorities, who only intervened later and sentenced him to prison.

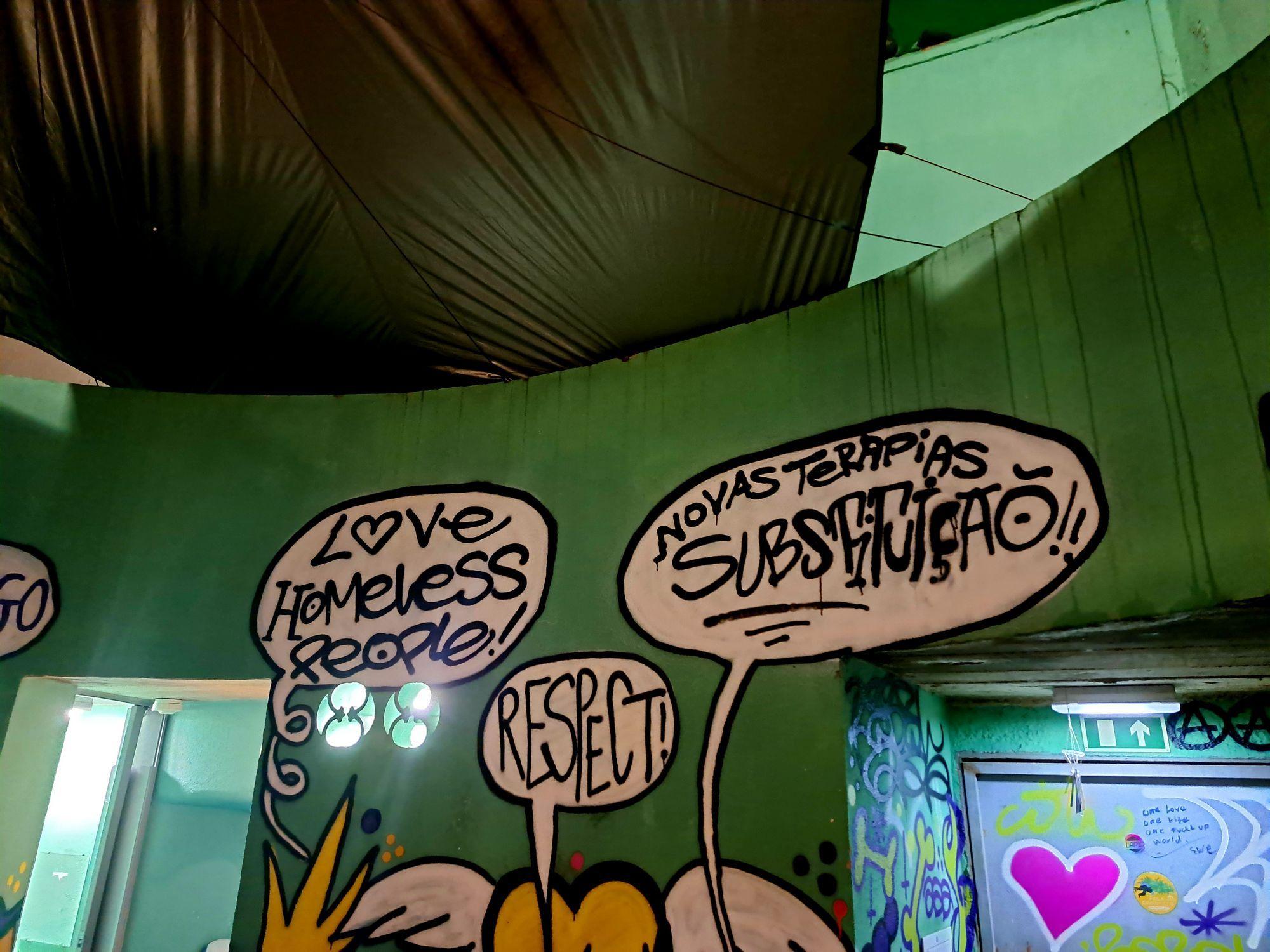

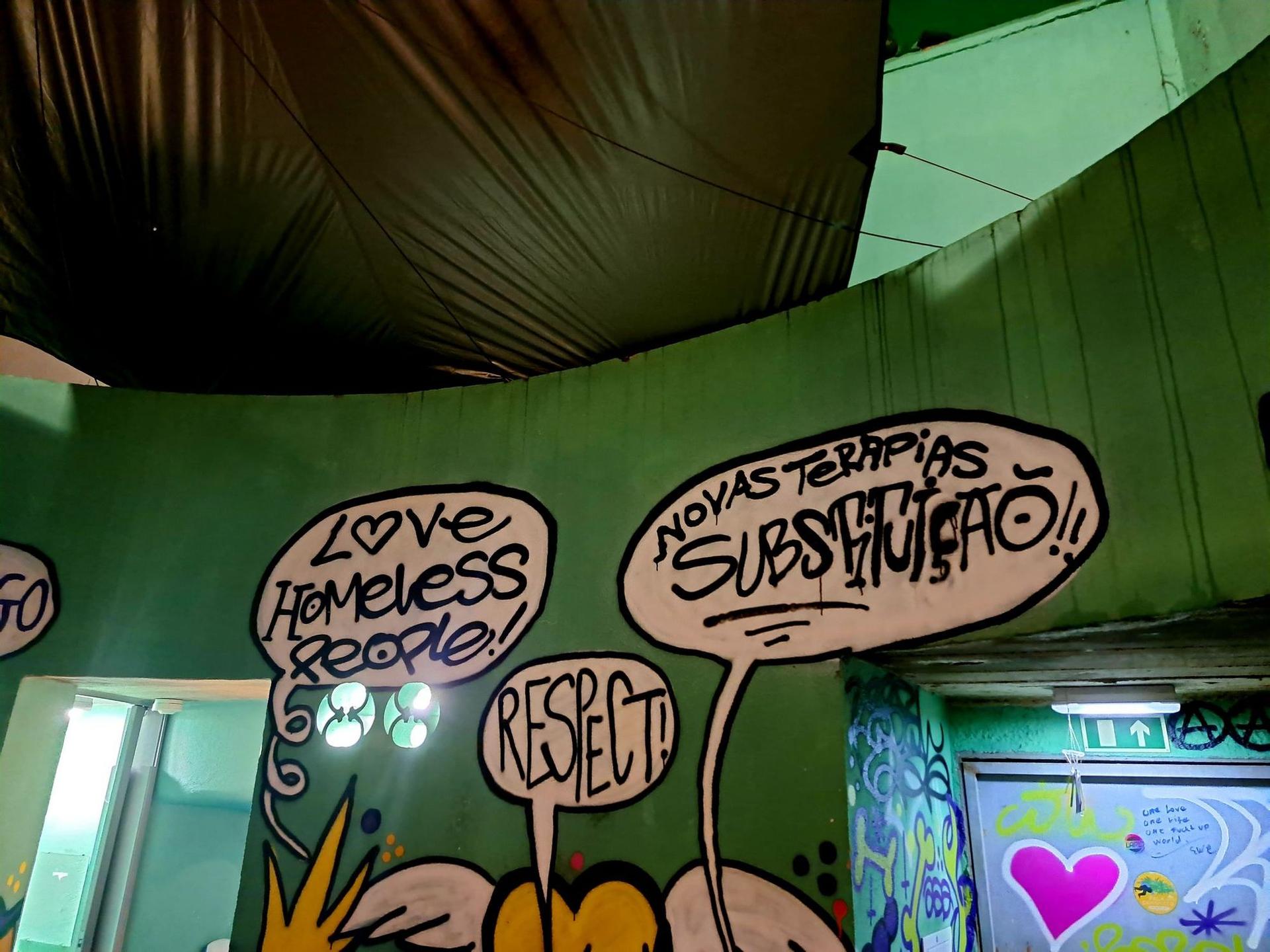

Tin foil, a Christmas tree decorated with syringes, pungent smoke. Behind the graffiti-painted metal door at 81 Calçada de Santo André, the air is dense. Inside there are about 20 people, men and women of different nationalities. They understand each other in whatever language they can, and the ambiance is generally calm. "Love homeless people", "Life is not a drug, but I like [drugs] a lot" or "Don't leave anyone behind" – these are some of the messages painted on the walls.

![Mural in the consumption room of IN Mouraria, painted by a group of French artists: "Life is not a drug, but I like [drugs] a lot"](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimg.pressone.ro%2F5gdZdhcqhxkGq_rlYpqcD-YfXRg%3D%2F2000x1500%2Fsmart%2Fhttps%253A%252F%252Fimages.pressone.ro%252Fwp-content%252Fuploads%252F2023%252F01%252F10115757%252F2.jpg&w=3840&q=75)

Mural in the consumption room of IN Mouraria, painted by a group of French artists: "Life is not a drug, but I like [drugs] a lot"

![Mural in the consumption room of IN Mouraria, painted by a group of French artists: "Life is not a drug, but I like [drugs] a lot"](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimg.pressone.ro%2FonsR54hMmzSrqlY2yHFm7iGtGFQ%3D%2F1980x1485%2Fsmart%2Fhttps%253A%252F%252Fimages.pressone.ro%252Fwp-content%252Fuploads%252F2023%252F01%252F10115757%252F2.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

Mural in the consumption room of IN Mouraria, painted by a group of French artists: "Life is not a drug, but I like [drugs] a lot"

Un newsletter pentru cititori curioși și inteligenți.

Sunt curios

This is what one of the two supervised drug consumption rooms in Lisbon looks like, opened two years ago and run by GAT (Grupo the Ativistas em Tratamentos), a non-governmental organisation working with people infected with HIV or at risk of getting infected.

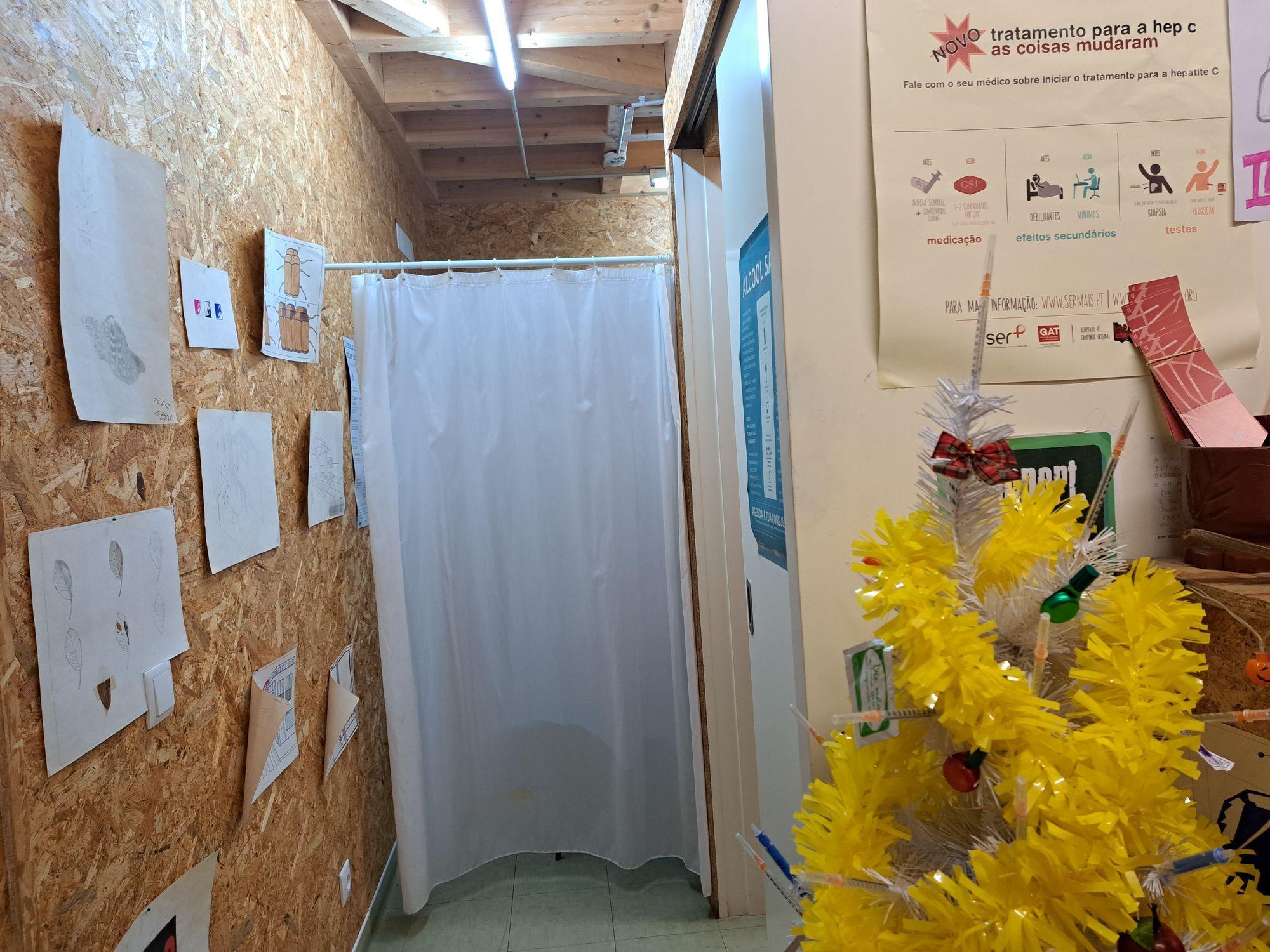

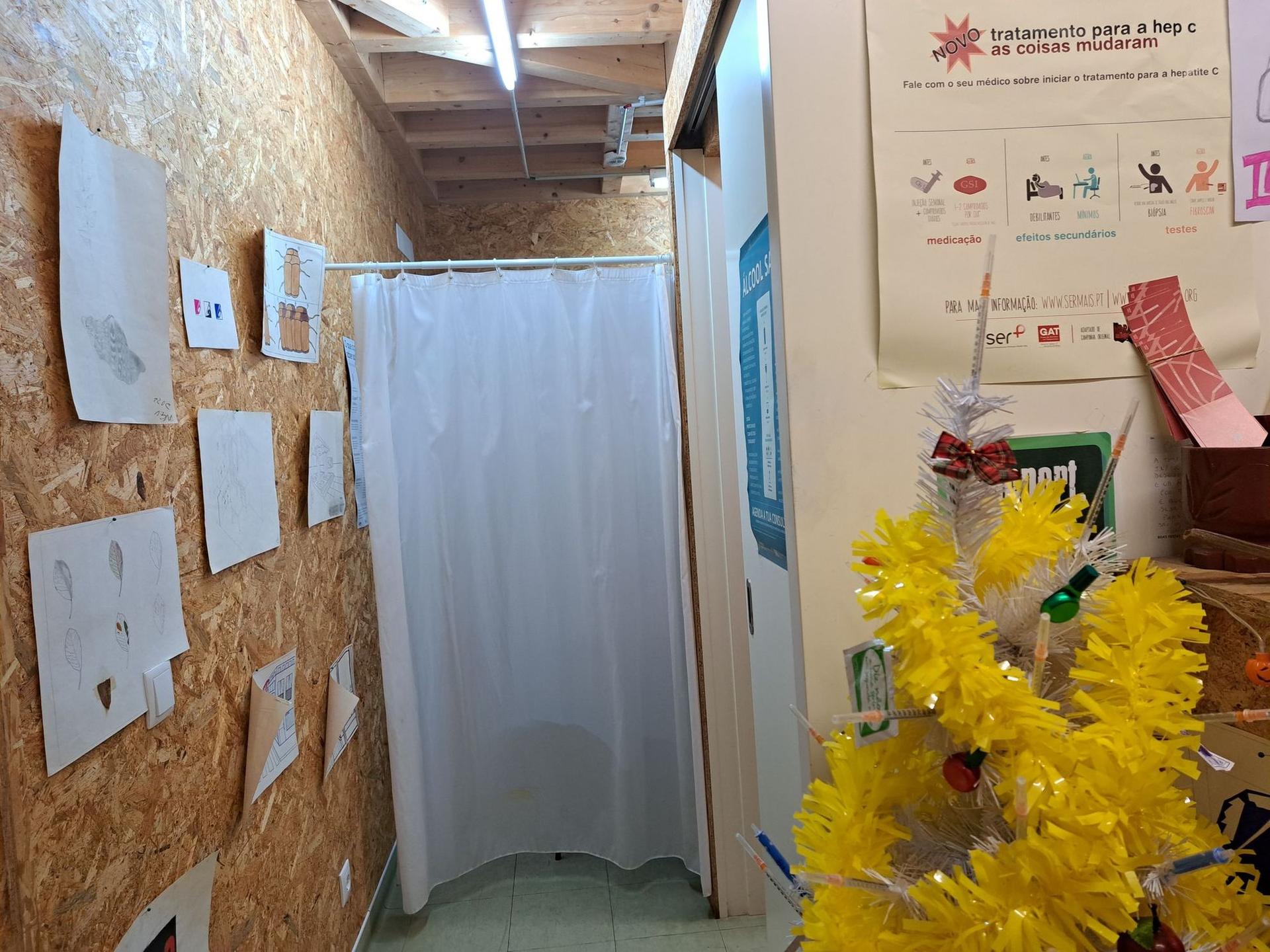

Well, improperly said room. It's more like a sort of terrace covered only with a tarpaulin, which isn't exactly effective in sheltering those inside from the rain that has just started. This area is reserved for smoking. At the back, a few steps lead up to a room divided into a reception area, a small consulting room and an injection room, hidden by a hospital curtain.

For a brief moment, music is discussed. Names like Stevie Wonder, Jim Morrison and Ray Charles pop up. Every five minutes or so, there's a loud knock on the door. Luisa Salazar, the centre's coordinator, or Malu, as she is known here, asks those who have been staying for a longer time to leave. It's someone else's turn now.

The newcomers enter and greet Malu with a smile. Some in Portuguese, others in English. Some are homeless, others look like they've just finished their workday at their corporate job, carrying laptops in their backpacks. Malu asks them how they're doing, then asks for their registration number and the type of substance they're about to consume. She writes them down in a table. For some of them, she already knows the number by heart.

"Fuck drugs!" shouts Paolo, by far the most cheerful one here, and looks at me with a smile, after learning that I am a journalist.

What Does the Decriminalization of Drugs Mean?

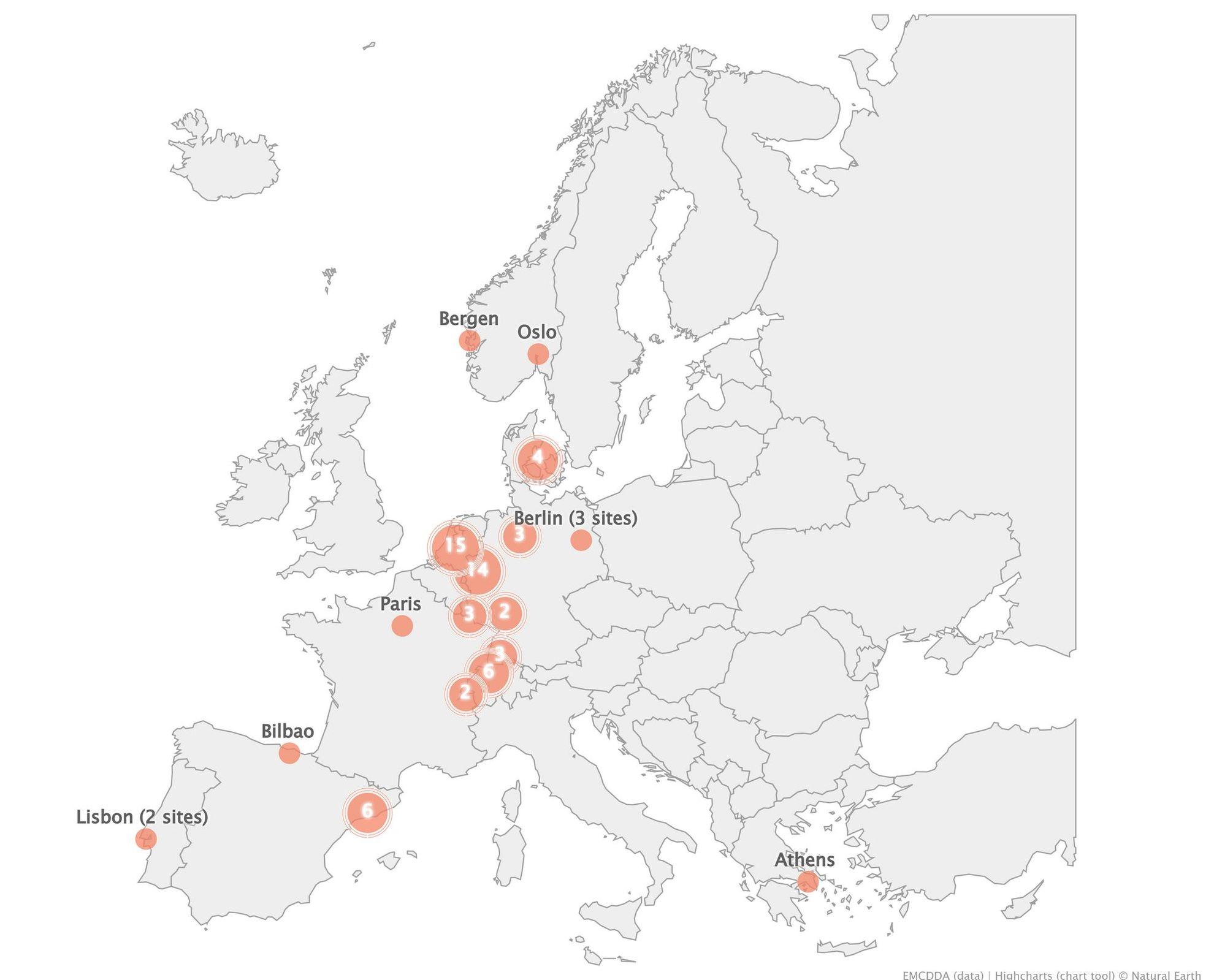

Dedicated supervised drug consumption (DCR) units have been operating in Europe for three decades. The first was opened in Bern, Switzerland, in 1986. Today, consumption rooms can also be found in France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, Norway, Spain and Greece.

These facilities aim primarily to reduce acute risks of disease transmission through unsafe injection, prevent overdose deaths, and connect high-risk drug users to addiction treatment and other health and social services. They also help reduce drug use in public places and associated problems.

Although it was among the last countries to join the DCR club, opening the first consumption room only in 2018, Portugal is a special case in Europe when it comes to dealing with drug use.

In 2001, the Iberian country became the first in the world to decriminalise the use of all drugs (Law 30/2000). Under this law, the purchase, possession and consumption of drugs are not legalised, just simply no longer subject to prosecution or imprisonment. Thus, the country has completely shifted towards a drug harm reduction approach.

Brendan Hughes, senior specialist on drug legislation at the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), explains for PressOne that other European countries took important steps towards a harm reduction approach before Portugal – needle exchange programmes or decriminalisation initiatives existed in Europe before Portugal implemented them. But what sets the Iberian country apart from others is that it was the first to restructure its system altogether, instead of making small adjustments to the law.

„The thing that Portugal did where it was absolutely a pioneer was to change their administrative structure so that a drug user would still found by the police - the police are first on the scene for anything - but they are not dealt with by somebody who is under the Ministry of Interior or Ministry of Justice. All other countries still have that”, the specialist explains.

Luisa Salazar, coordinator of the IN Mouraria centre, asks for the registration numbers of new arrivals in the consumption room

Luisa Salazar, coordinator of the IN Mouraria centre, asks for the registration numbers of new arrivals in the consumption room

Anyone caught with up to 10 days' worth of any drug – from cannabis to heroin – is invited to meet with a local board, made up of a doctor, a lawyer and a social worker, where they are informed about available treatment and medical services.

The results of this system, according to the deputy director of SICAD (the institution that monitors addiction) interviewed by PressOne, show that 97% of these people report to the commission and around 75% change their relationship with drugs.

The law makes no distinction between "hard" and "soft" drugs, or whether use takes place in private or in public. What matters is whether the relationship with drugs is healthy or not. Drug dealers, on the other hand, are in no way benefiting from this law; they are still being prosecuted.

The makeshift roof over the consumption room

The makeshift roof over the consumption room

One of the core ideas of the Portuguese model is that no matter what the state does, drug addiction will continue to exist and affect citizens. What the 2001 legal change brought about was the implementation of a system where the addict is no longer considered a criminal, but a person with a health issue who needs help.

Decriminalisation is merely the first step, one that makes it easier for specialists to reach those in need. It also removes much of the stigma associated with drug addiction and encourages those in this situation to get help, both on the street, from mobile teams and in centres like IN Mouraria.

"If I could go back, I'd take a different path"

"We have a safe and free of judgement space here", Malu tells me as she leads me to the other side of the IN Mouraria centre. Here, the door is always open and leads to a large room, a communal space with sofas, tables, computers and a medical office.

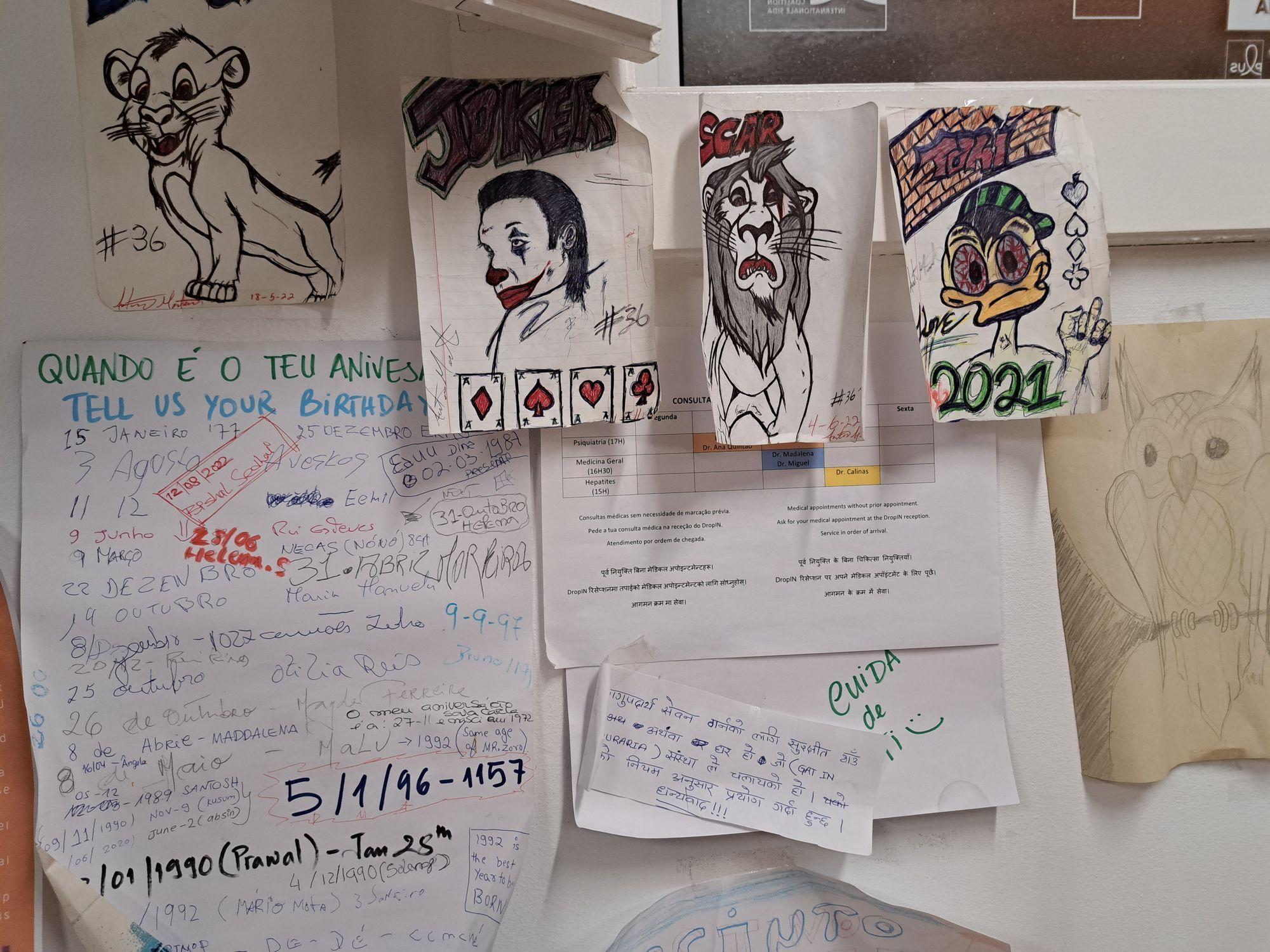

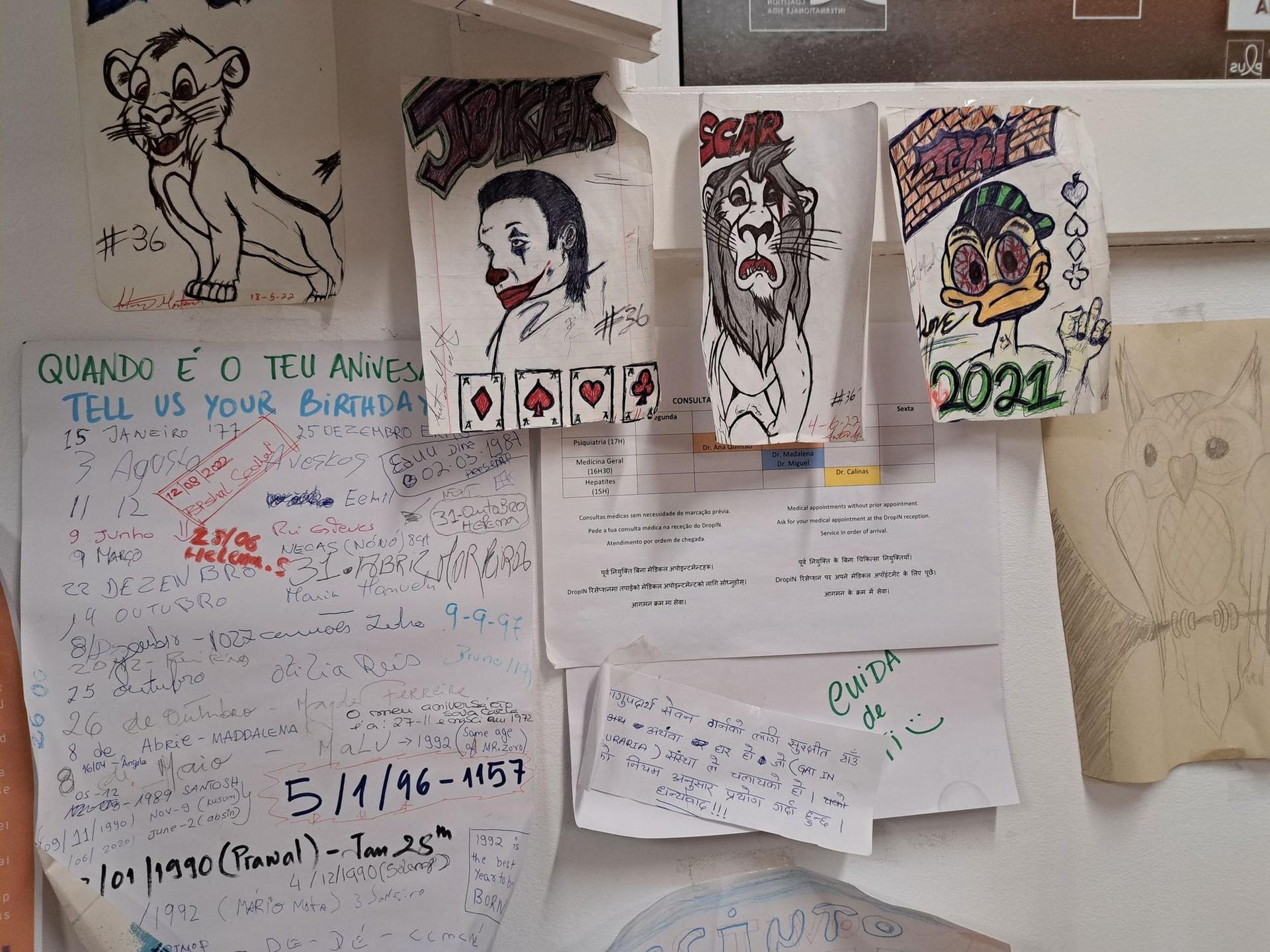

This is where people who come to the centre for the first time arrive, but it's also where regulars come to deal with paperwork, pick up their mail and spend time together or participate in activities organized by GAT. Drawings made by people from the community decorate the walls.

Some of the consumers who come to the GAT centre also bring their pets. This is Zeus in the consumption room

Some of the consumers who come to the GAT centre also bring their pets. This is Zeus in the consumption room

The centre's permanent staff consists of three nurses, two social workers and four peers – people who have experienced addiction and can offer support and advice to consumers. In addition to them, there are several volunteers, mostly students. Malu estimates that between 60 to 80 people come to IN Mouraria on a daily basis.

One of them is Ionuț. Malu introduces us in the consumption room, where he is called João. At first, Ionuț looks at me suspiciously. He can't quite get himself to believe that he can speak to someone in Romanian. He communicates with the people around him in Spanish. But speaking his native tongue seems to convince him to open up.

A hospital curtain separates the injection room from the rest of the supervised consumption unit

A hospital curtain separates the injection room from the rest of the supervised consumption unit

Whenever the conversation veers towards his addiction, Ionuț becomes tense:

"Drugs took everything from me. If I could go back, I'd take a different path", that's all he tells me, then changes the subject again. We talk about our homes, about the food he misses, about the death of his father - which he wasn't close to, but Ionuț still affected by his loss. And about God.

- I got to a point where I thought I could sell drugs. But I realised that God sees us and...

- Are you a believer?

- So-so. I was, you know, but now, with all the things I've seen and done...

- You're not sure anymore?

- Well, there must be something out there. I can't believe we're really alone.

When I ask him if he has friends, or if he feels at home here, at the centre, Ionuț replies almost automatically: No. Yet he comes here almost every day, according to Malu. And when a familiar face appears, Ionuț stands up and asks: Que tal, hermano?

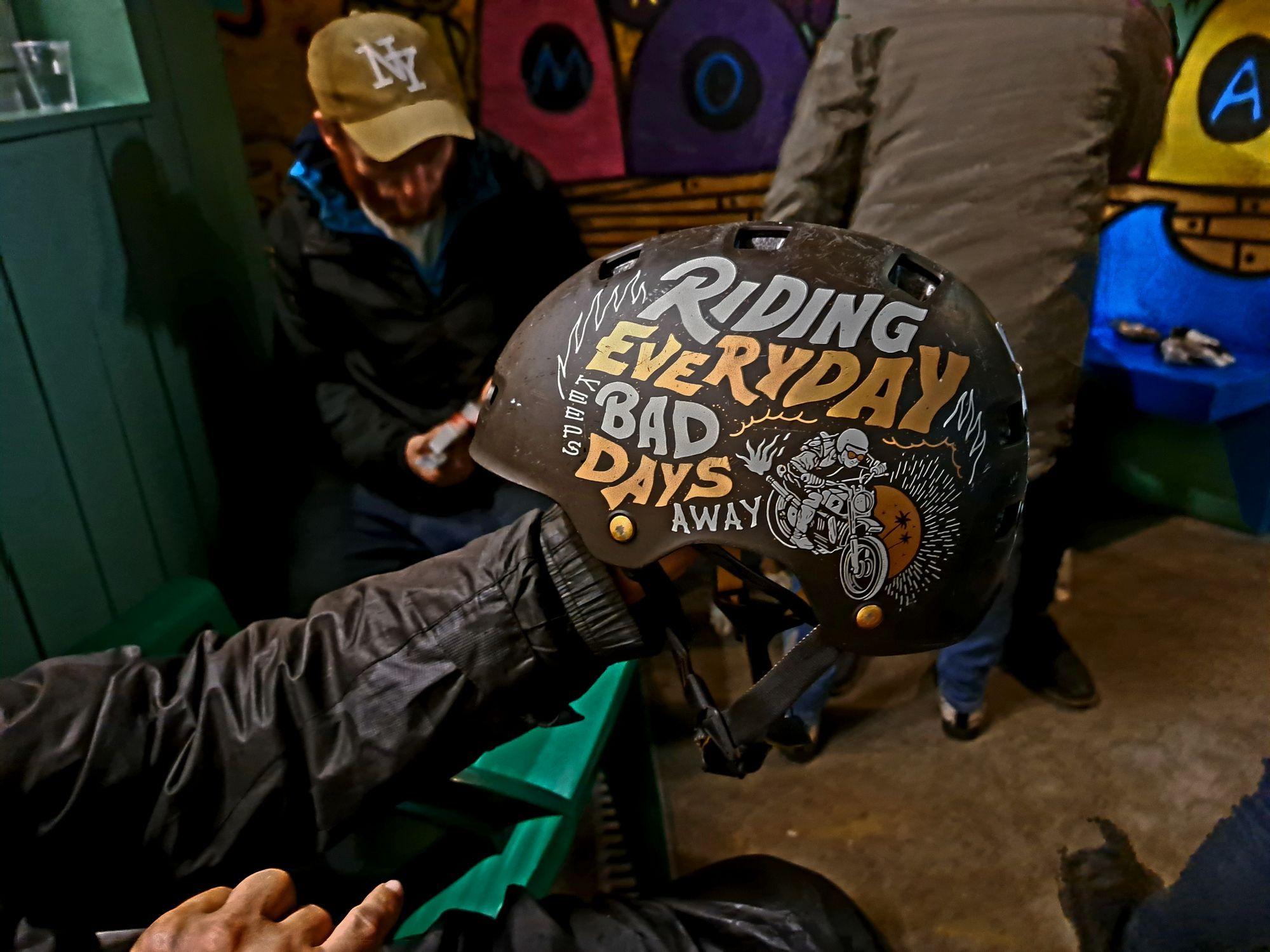

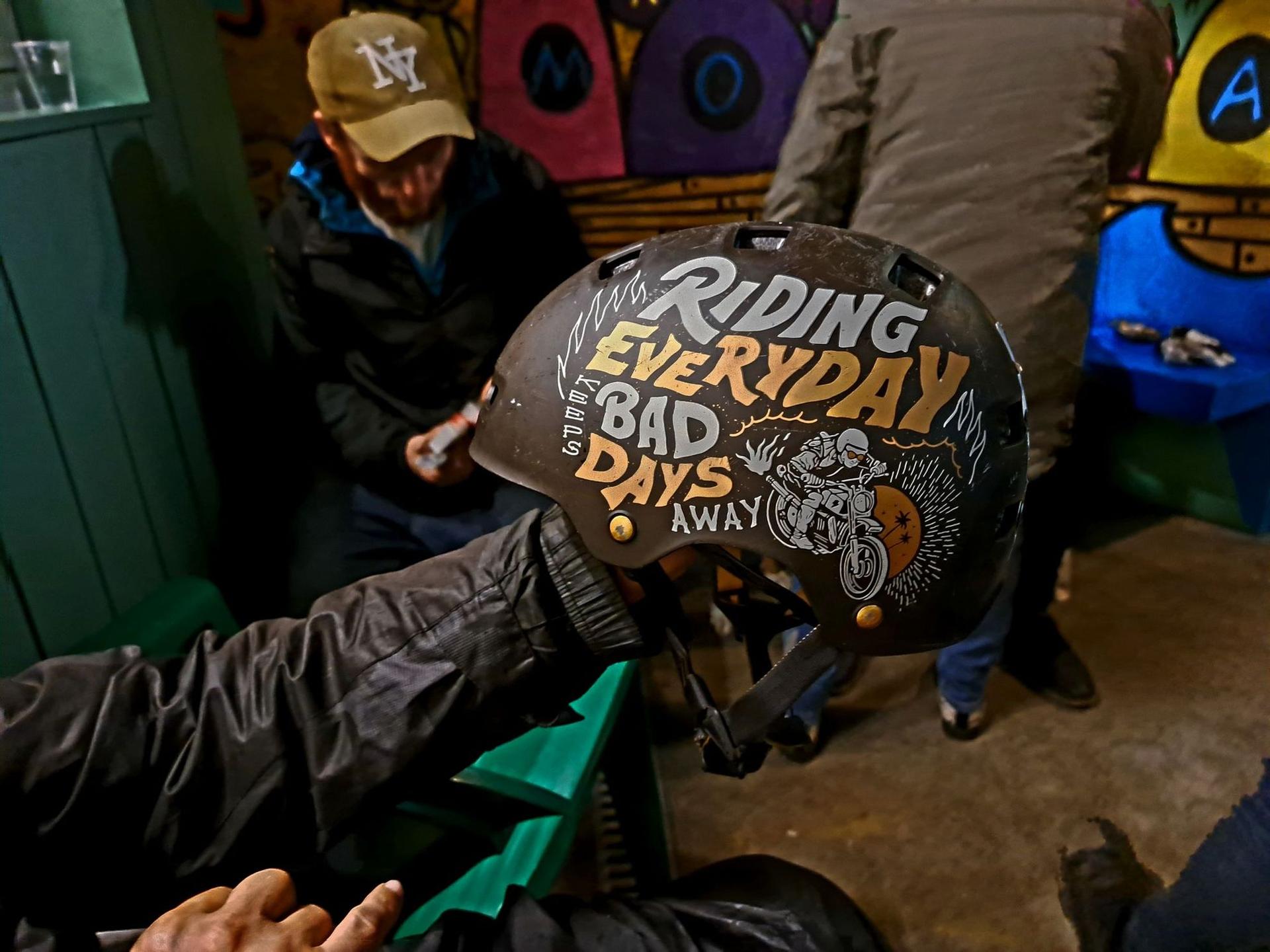

Paolo, a regular at the GAT centre, proudly shows off his motorcycle helmet

Paolo, a regular at the GAT centre, proudly shows off his motorcycle helmet

He asks for my phone at one point. He wants to call his mother. He struggles for a while, but eventually he remembers the number and someone on the other end answers. A calm woman's voice, to which Ionuț speaks softly, almost in a whisper.

- Hello?

- Hello, Mom... It's Ionuț.

- Yes? What have you been up to, my boy?

- Look, a girl gave me her phone and I thought I'd call you...

An announcement comes from the other side of the center: yoga class is starting. But no one in the consumption room seems very enthusiastic about the idea. Least of all Ionuț, who has retreated to a corner with my phone.

"There was a gap between the community and the law"

To understand how Portugal came to radically change its approach to drug use in 2001, PressOne spoke to Dr. Manuel Cardoso, Deputy Director of the General Directorate for Intervention on Addictive Behaviour and Dependencies (SICAD).

The specialist recalls that in the 1990s, one of the biggest problems in Portuguese society was heroin addiction. About 1% of the population was addicted, and this percentage was spread across multiple social categories. Moreover, Portugal had the highest rate of HIV infection in the European Union.

"At that time, from our information on HIV infections, around 60% were drug addicts or users. It was a huge problem. We used to say that everyone had at least one relative who was dealing with this problem", Cardoso says.

In this context, the government led by socialist prime minister António Guterres (now UN Secretary-General) decided to set up a commission to discuss, assess and propose a strategy for dealing with the problem. The aim was a comprehensive approach, including prevention, treatment, reducing the medical risks associated with consumption and reintegrating addicts into society.

Drawings by IN Mouraria community members

Drawings by IN Mouraria community members

"We realised that it was very difficult for specialists to work with drug addicts because the law was very restrictive and drug use was a crime. Also, even back then, the Portuguese society saw addicts more as ill people than as criminals. So between the community and the law there was a gap", he explains.

The commission proposed decriminalisation as a measure to make it easier for addicts to access a wide range of services (medical, psychiatric, employment, housing etc.) The government adopted the commission's plan "almost line by line", Dr. Cardoso says.

The Results of the Portuguese System

With time, positive developments become clear. A study from 2021 mentions, as results:

- a reduction in mortality and infections associated with addictive behaviour;

- a postponement of the age of initiation and an increase in the perception of associated risks among young people;

- a reasonably low level of drug use compared to most European countries.

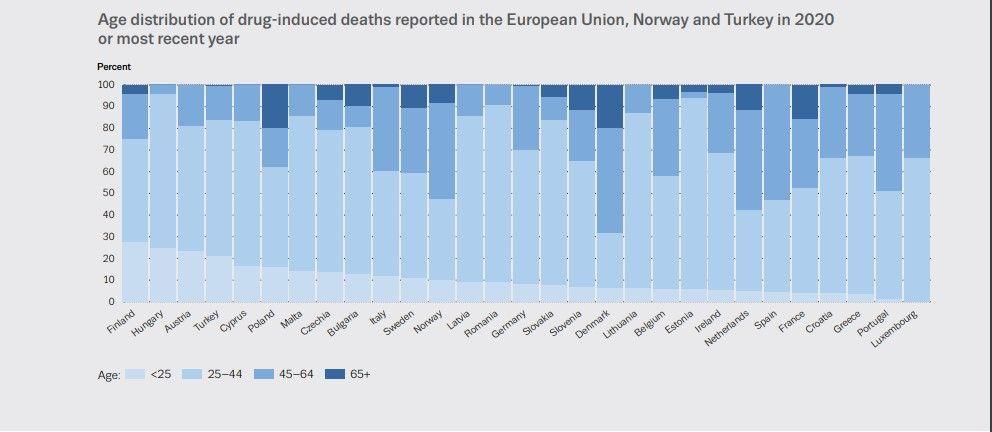

And in the latest European Drugs Report (2022) Portugal shows lower figures than the European average for consumption in all drug categories. Also, many European countries (such as Denmark, Norway, Greece or Sweden) had more than 30 drug-related deaths per million inhabitants in 2020. In comparison, Portugal had only 10, which is below the European average of 16.7.

As for HIV infections, Dr. Manuel Cardoso says that from 60% in 2000, today only 2% of reported infections come from drug users. At the same time, UN data from the last ten years show an overall decline in HIV infections and related deaths in Portugal.

The "Results" of the Romanian System

Unlike Portugal, in Romania the drug phenomenon is mainly managed by the Ministry of Internal Affairs, through the National Anti-Drug Agency (ANA).

According to the latest data reported at European level, Romania remains at the bottom of the chart in terms of drug use, even though prevalence has increased in recent years. The official figure would indicate 1.2 million occasional or dependent users nationwide, but the accuracy of the data is questioned by the state's monopoly on reporting through ANA, the only institution that does such reporting.

What both the latest European report and the most recent ANA study show is an increase in drug use in the 15-34 age group. We have the highest percentages in Europe for psychoactive substances (5.1%) and ketamine (0.8%) use among young people.

At the same time, Romania has 1.9 drug-related HIV cases per million inhabitants in 2020, above the European average of 1.3. We also have an overwhelming prevalence of injecting as a method of opioid use: 80.8% in Romania, compared to a European average of 30.8%.

But in terms of drug-related deaths, we are apparently doing well. In 2020, Romania reports only 3 deaths/million inhabitants, compared to a Europe-wide prevalence of 16.7 deaths/million.

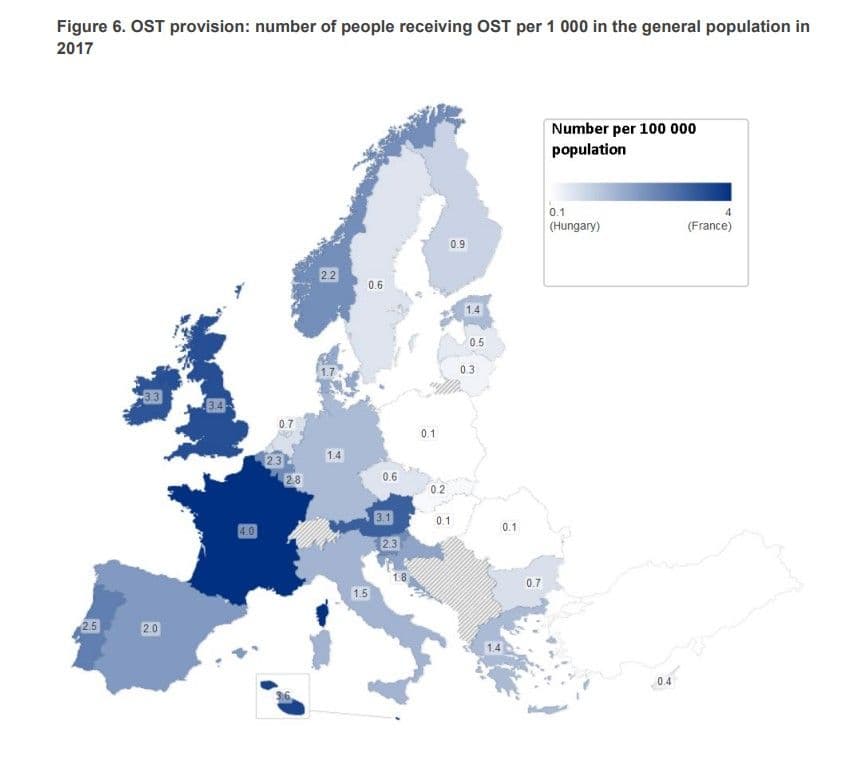

Romania is also among the last countries in the EU in terms of distribution of opioid substitution treatment (OST): only 10% of users receive such treatment, according to an EMCDDA technical report. At the opposite end, in Slovenia, Greece or France at least one in two consumers receive OST.

Romania currently has no public centre for the treatment of addictions. As PressOne reported last year, the field of care, prevention and treatment of drug addiction, as well as policy-making, is completely divorced from medical factors, medical and psychological specialists.

Ionut frantically searches for the tin foil he dropped on the floor, under the light of my phone's flash.

"At first you do it out of curiosity, then out of desire and then... out of need", he tells me with a bitter smile.

It's hard to spend time in a place like this. It's even harder to work in this environment every day, trying to help the people who have chosen this path.

"Burnout is always around the corner when you work here", Malu tells me. That's why the centre's staff receive psychological counselling and supervision in the consumption room is done by rotation. Besides, things don't look as rosy here, at ground zero, as they do in SICAD reports and statistics.

Luisa Salazar, Malu, says what motivates her in her work at the centre is the community that has grown up around it

Luisa Salazar, Malu, says what motivates her in her work at the centre is the community that has grown up around it

Malu talks about insufficient staff, necessary equipment provided from the NGO’s own small budget, the lack of resources for ubstance testing in the Mouraria centre. But all these problems point to a central one: underfunding. When I ask her what motivates her in her work at the centre, despite all these difficulties, Malu answers without thinking: the community they have managed to create here. The people.

"An addict for us is a sick person, not a criminal. If you look at him and try to treat him like a sick person, everything changes. That's the big difference. Look at the people, the citizens, this individual. What's his problem? How can we manage the problem and find a solution to it, no matter the substance, no matter the behaviour? Look at the people." - Dr. Manuel Cardoso, Deputy Director of SICAD

Avem nevoie de ajutorul tău!

Mulți ne citesc, puțini ne susțin. Asta e realitatea. Dar jurnalismul independent și de serviciu public nu se face cu aer, nici cu încurajări, și mai ales nici cu bani de la partide, politicieni sau industriile care creează dependență. Se face, în primul rând, cu bani de la cititori, adică de cei care sunt informați corect, cu mari eforturi, de puținii jurnaliști corecți care au mai rămas în România.

De aceea, este vital pentru noi să fim susținuți de cititorii noștri.

Dacă ne susții cu o sumă mică pe lună sau prin redirecționarea a 3.5% din impozitul tău pe venit, noi vom putea să-ți oferim în continuare jurnalism independent, onest, care merge în profunzime, să ne continuăm lupta contra corupției, plagiatelor, dezinformării, poluării, să facem reportaje imersive despre România reală și să scriem despre oamenii care o transformă în bine. Să dăm zgomotul la o parte și să-ți arătăm ce merită cu adevărat știut din ce se întâmplă în jur.

Ne poți ajuta chiar acum. Orice sumă contează, dar faptul că devii și rămâi abonat PressOne face toată diferența. Poți folosi direct caseta de mai jos sau accesa pagina Susține pentru alte modalități în care ne poți sprijini.

Vrei să ne ajuți? Orice sumă contează.

Share this