After 18 hours on the night train, Keleti station appears timidly in the window, like a mirage.

It's only when the cold, damp air hits my face that I realise I've finally arrived in Budapest.

It's drizzling and it's cold. If it weren't for the blossoming trees, you'd swear it was November, not late March.

After 18 hours on the night train, Keleti station appears timidly in the window, like a mirage.

It's only when the cold, damp air hits my face that I realise I've finally arrived in Budapest.

It's drizzling and it's cold. If it weren't for the blossoming trees, you'd swear it was November, not late March.

Hungarian Parliamentary Elections 2022. How Sunday's Optimism Turned Into Monday's Pessimism

English Section

02/05/2022

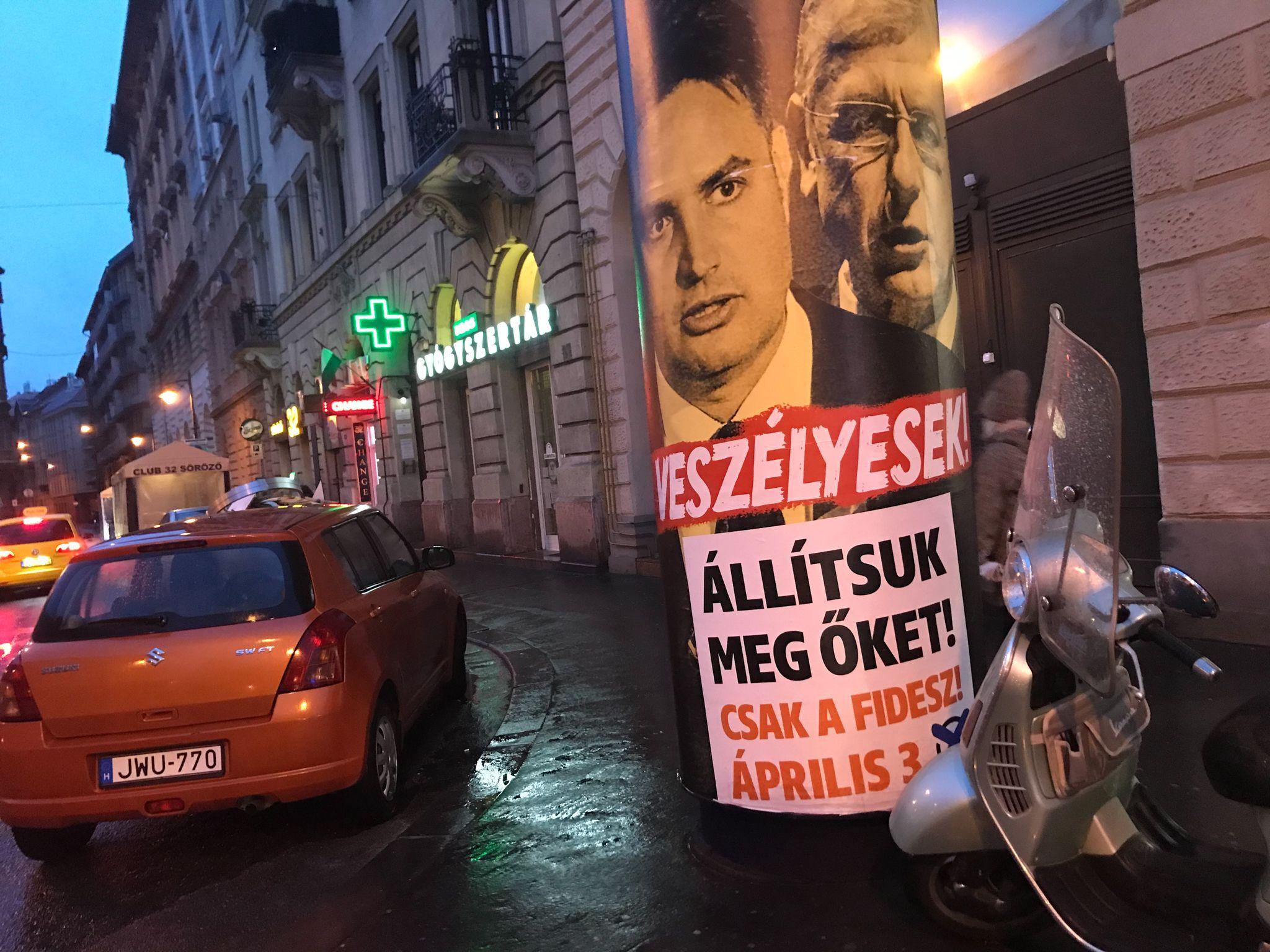

You might be in Budapest for the first time, but you certainly wouldn't be able to miss the fact that something is about to happen in the city.

A politician is watching you from every lamppost on the street.

It's Thursday, March 31st, 2022 - four days until the parliamentary elections.

Before Sunday's elections, the nationalist Fidesz party, led by Prime Minister Viktor Orban, had a two-thirds majority in the Hungarian Parliament. This has been the case for the last 12 years, more than a decade which has allowed it to change organic laws at will, including those governing the electoral process. And it did so as soon as Orban came to power. The consequence? In the 2014 elections, Fidesz won the same number of seats in the Parliament, despite having only 45% of the vote.

But this year's elections were different. For the first time in 12 years, Fidesz finally had an opponent that seemed to be a match for it: the Egységben Magyarországért (United for Hungary), a coalition of six opposition parties spread across the political spectrum, from the social democrats MSZP to Jobbik, a former far-right party converted to more moderate conservatism. Top of their list and Orban's direct opponent was Péter Márki-Zay, mayor of Hódmezővásárhely, a small town closer to Timișoara than Budapest.

The latest poll, conducted by Zavech Research, put Orban's Fidesz just a few percentage points ahead of the coalition. The race appeared to be close.

But on Sunday, Viktor Orban won his fourth consecutive term as head of government.

Mulți ne citesc, puțini ne susțin. Fără ajutorul tău, nu putem continua să scriem astfel de articole. Cu doar 5 euro pe lună ne poți ajuta mai mult decât crezi și poți face diferența chiar acum!

This is what we saw on the streets of Budapest, on the weekend of the parliamentary elections on April 3 2022.

Budapest, a bubble for people who want to change the system

Palma is 33 years old and has a contagious smile. She has travelled extensively in Europe, and even worked for a few years in Switzerland, but chose to return home to Budapest, where she now owns a small business selling clothes printed with designs from local artists.

"I chose to come back because I love Hungary and I really hope for a change. Because I love living here."

Predator in Robes: The Diocese of Iași and the Vatican Buried a Sexual Assault Committed by a Catholic Priest Against a Minor in Bacău, Failing to Alert Prosecutors

A Roman Catholic priest abused a 13-year-old girl in the parish where he served in Bacău County: the bishop of Iași knew about it, sent the case to the Vatican, and applied canonical sanctions, but did not notify the authorities, who only intervened later and sentenced him to prison.

She says it sincerely, wholeheartedly, from behind the counter of her small showroom in the centre of Budapest. When I ask her what's happening in the city these days, she starts straight away with Sunday's elections.

Palma, 33 years old

Palma, 33 years old

PressOne: Are you going to vote? What are your expectations?

Un newsletter pentru cititori curioși și inteligenți.

Sunt curios

Palma: Of course I'm going to vote. I'm more in favour of the opposition, but unfortunately I don't give them much of a chance. The problem is that the MSZP, who were at the head of the government before Fidesz, screwed up badly. They should have disappeared. But they're still here, and that spoils the whole thing.

Another thing is that here in Budapest we really live in a bubble. We are against this government. But to be honest, I don't believe so much in the opposition either. I just choose the lesser evil.

PressOne: Do you think young people in Hungary are interested in this election? Are they motivated to vote?

Palma: Yes, of course they are. I think they are very interested in voting because they want to change the system. They are suffering. The education system is messed up, teachers are not paid. Young people don't see a good future here in Hungary. Many want to leave because of low wages and lack of opportunities.

PressOne: In a recent statement, Viktor Orban said that the biggest stake in Sunday's parliamentary elections is whether Hungary gets involved in the war in Ukraine. What do you think, should Hungary get more involved or is it better to stay on the sidelines and preserve its relations with Russia?

Palma: I really hope that we have more than just these two options. I am very sad about the situation, I hate war. I don't want it in our country or anywhere near our country, and this is not about our relations with Russia. I don't care about that. I just want peace, and with the EU and the countries around us, and Russia. I know it's not easy, especially as we import a lot of gas from Russia. I've heard the EU talking about trying to get rid of our dependence on their gas. But that will take time. As an ordinary person, I hope there will be other options than choosing between Russia and Ukraine.

"There is no «relaxed» way to talk about these elections"

I had the same conversation with Marton and Rahel on Thursday evening before a local band concert. He's 24, she's 22. He's dressed in head-to-toe black, she's wearing a red pleated skirt and white booties. Of all the people gathered in Turbina, a former industrial space turned into a maze-like club, they were the only ones open to talking about Sunday's election.

"There's no relaxed way to talk about this subject," someone slammed me. People in Budapest come to places like this to escape from everyday problems, not to discuss politics. This is also the case with Marton and Rahel. I can feel their tension from the first moments of the conversation. Only later I understand where it comes from.

Turbina, one of Budapest's industrial reinvented spaces. Since the war began, it's been turned into a daytime refugee centre

Turbina, one of Budapest's industrial reinvented spaces. Since the war began, it's been turned into a daytime refugee centre

"I heard a story from a friend who is doing research in a village near the Romanian border. He told me that there are a lot of buses coming from across the border with people who are not actually Hungarians and can vote because they have their residence on their ID card in Hungary. This is one of the reasons why I think Fidesz will win. They are not Hungarians, they are just paid," Rahel tells me.

She notices my scepticism, but assures me it's not fiction. Marton agrees and comes up with another example:

"There have been situations with buses coming from villages for Fidesz demonstrations. And people had no idea what they came here for. They were just paid. But I'm somehow optimistic about this election."

And he tells me the same thing Palma mentioned: that Budapest is an island of people who are fed up with Fidesz, and who now turn their hopes to the united opposition. Incidentally, the mayor of Budapest, Gergely Karácsony, belongs to the alliance's Green party.

"In the countryside the situation is exactly the opposite. It's quite hard to convince people that Fidesz is the wrong choice. For my family and many other families, this party has made life quite difficult. I won't say exactly how, it's quite personal. But I think the last 12 years have not been the most opportune for us," Marton confesses.

"If I tell people that my mother is a teacher and my father works in health care, they'll just laugh. These two are among the most important, and yet, among the lowest paid jobs in Hungary," she explains.

As for the war, Rahel is adamant: "I think this war has nothing to do with Hungary. Ukraine and Russia had a reason to start this war. The situation is not as simple as it seems. I can't fully support either Ukraine or Russia. I don't know what's going on there, but it doesn't smell good. Either way, innocent people don't deserve what's happening."

He finishes his sentence along with his cigarette and sighs. Then his face lights up. The concert begins, time to put politics aside. In a few minutes I lose them both in the crowd.

Between war and so-called "neutrality". Between Russia and the West. The stakes of the Hungarian parliamentary elections

The April 3 parliamentary elections have multiple stakes, and the results will reverberate far beyond Hungary's borders. After two difficult years in which the country has had among the highest death rates in the EU from the pandemic, inflation has soared. Orban's government has been in constant conflict with the EU over his party's controversial rule of law. These elections are shaping up as the chance to end the illiberal democracy of Fidesz and turn the tiller towards the West.

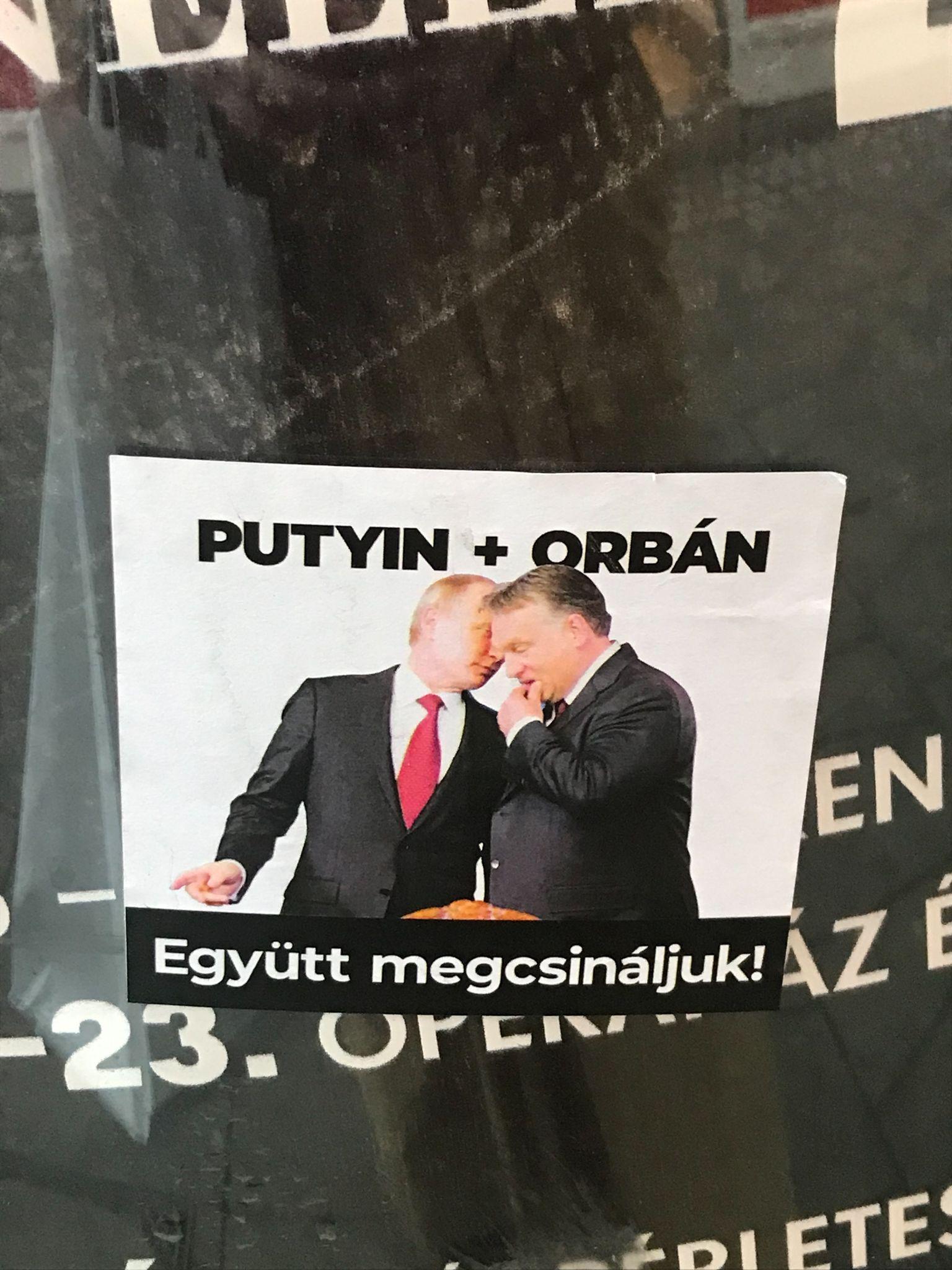

Vladimir Putin's war in Ukraine gives even more weight to the vote and has naturally become the central theme of the election campaign, capitalised on by both sides. Orban portrays it as a choice for Hungarians - whether to go to war or not, while his opponent, Péter Marki-Zay, has called it a choice between Russia and the West. Somehow, both of them are right.

There is at least one election poster on almost every lamppost in Budapest. Here, Fidesz (top) and the coalition of opposition parties (bottom)

There is at least one election poster on almost every lamppost in Budapest. Here, Fidesz (top) and the coalition of opposition parties (bottom)

Orban's victory - for the fourth time in a row - would mean, at this point, that Hungary openly embraces a pro-Russian political agenda. After all, this is the man who is considered to be Putin's most trusted ally in Europe, the one who makes sure that Moscow's propaganda is heard loud and clear in Hungary, in exchange for a cheap gas subscription.

As much as the prime minister has tried to feign neutrality and convince Hungarians that the war is not their concern, the truth is that Hungary's international relations are more vulnerable than ever in the context of the war, as Wojciech Przybylski, editor-in-chief of Visegrad Insight, points out for Politico. Viktor Orban's counterparts from the Czech Republic, Slovenia and Poland visited Ukrainian President Volodimir Zelenski in Kiev. Orban, instead, accused him of meddling in Hungary's internal politics, after Zelenski addressed him directly in a video message, asking him to decide whose side he was on.

While the outcome of the election is hard to predict because of Hungary's electoral system, which capitalises on even the smallest percentage advantage in favour of the strongest party, it is certain to determine the political dynamics in Eastern Europe for the next few years.

The small parties are out in the streets, among the people. Fidesz is not

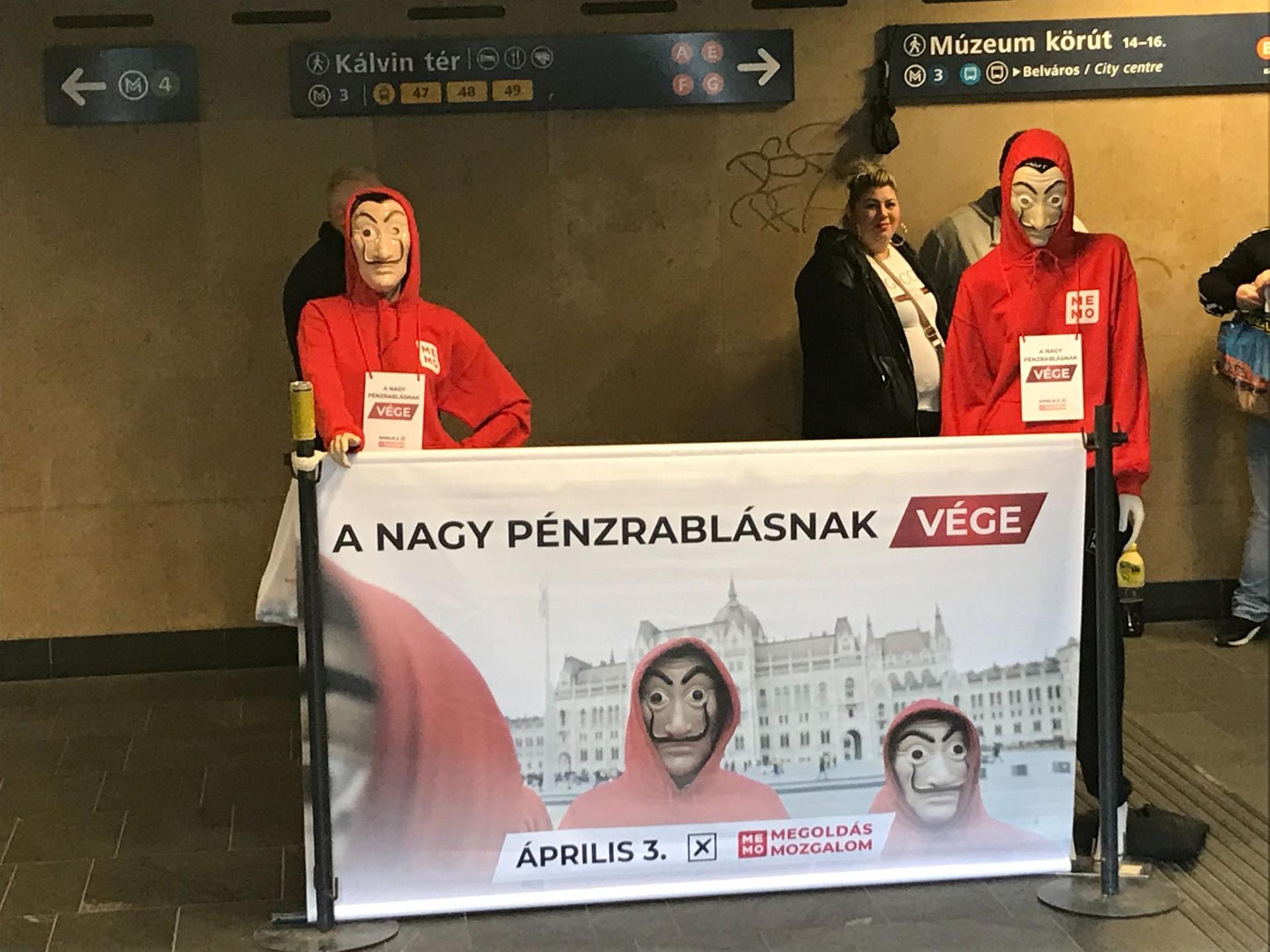

On Friday morning, the area around Kálvin tér metro station seems under siege. Thirty or so people in red hoodies mill about, stand in parallel lines then scatter again as a voice blares from a megaphone.

You can only see some of their faces: the rest are covered by masks with Dalí's face. They are supporters of the MeMo party and have chosen the TV show "La Casa del Papel" as an analogy for the economic measures they propose. They are also in the opposition, but not part of the coalition. MeMo is a very young party, founded by György Gattyán, one of Hungary's wealthiest men, just a few months ago.

Vineri, 1 aprilie 2022. Standul partidului MeMo în stația de metrou Kalvin

Vineri, 1 aprilie 2022. Standul partidului MeMo în stația de metrou Kalvin

But if they pass the 5% threshold and enter the Hungarian Parliament, the two big powers may have to negotiate with them in order to get a majority. Because of alleged links with Fidesz, some believe the party was formed solely to hamper the coalition.

This is the case with Zoltan, who wears two purple badges on the collar of his jeans jacket, which he proudly shows me. He came to the MeMo people to ask them how they would tackle inflation. When I ask him how he would describe this year's elections, he replies with the refrain that has been circulating for years in the international press when it comes to Hungary's electoral process: "It's a free election, but it's not a fair fight."

"Opposition candidates were entitled to five minutes of speaking time in the televised debates. Fidesz gets constant publicity. Even so, I think there's a good chance they won't be in power after this election," says Zoltan.

Friday, April 1, 2022, in front of Kalvin metro station. Supporters of the MeMo party

Friday, April 1, 2022, in front of Kalvin metro station. Supporters of the MeMo party

A special appearance on Sunday's ballot paper, and a fairly rare one on the posters on the lampposts, is the satirical Two-Tailed Hungarian Dog Party. Yes, that's exactly what it's called. On their posters you don't see a smug politician smiling, but… a dog with two tails, just as a five-year-old would draw it.

On Sunday, election day, I came across one of their stalls outside a shopping mall. They weren't trying to get people to vote, but their tent was crowded. They were collecting donations for Ukraine and offering support for refugees.

In front of Keleti station, I am approached by two ladies in white capes, in their 40s and 50s. They come from behind a stall from which Péter Márki-Zay is smiling. They are from the coalition, the ones that Orban calls "communists" today, on election day. They are doing exactly what he was afraid they would be doing: urging people to go and vote. After they hear me say "Hello", they stop talking. They laugh, then ask me in a British-accented English what I'm doing in Budapest.

"Ah, you work for independent media! That's great. We don't really have that," one of them tells me with a smile.

There's no tension in them, even when I ask them what they think the coalition's chances are. They are confident, people are actually going to vote. And here in Budapest, that mostly means votes for the coalition or at least against Fidesz. Maybe that's the reason why at 3 p.m., when I said goodbye to Budapest, almost 57% of its inhabitants had already voted. Nationally, the turnout was also good: more than half of the country's population.

A poster of a candidate on the Fidesz list, right next to a billboard with a caricature of Putin, at an exhibition in solidarity with Ukraine

A poster of a candidate on the Fidesz list, right next to a billboard with a caricature of Putin, at an exhibition in solidarity with Ukraine

Viktor Orban's party didn't bother to take to the streets of Budapest in the four days before the elections. It remained a latent presence, in street corner posters, on metro station walls and in the collective mind of the people.

While the opposition works in the shadows, Fidesz looks on defiantly from the windows of its magnificent palace on the banks of the Danube. When you have power, you have much more effective methods at your disposal: media control and smear campaigns are amongst them.

Methods that turn out to be more effective in the end: at midnight, on the same day, Orban declares his victory, "that can be seen even from the moon, but especially from Brussels".

After all the votes had been counted, Fidesz had once again secured a two-thirds majority in the Hungarian parliament: 135 seats out of 199. The opposition only has 57. The far-right Mi Hazánk (Our Fatherland) party, the new Jobbick, has also entered parliament.

On the electoral map, Budapest remains a speck in an orange country.

Avem nevoie de ajutorul tău!

Mulți ne citesc, puțini ne susțin. Asta e realitatea. Dar jurnalismul independent și de serviciu public nu se face cu aer, nici cu încurajări, și mai ales nici cu bani de la partide, politicieni sau industriile care creează dependență. Se face, în primul rând, cu bani de la cititori, adică de cei care sunt informați corect, cu mari eforturi, de puținii jurnaliști corecți care au mai rămas în România.

De aceea, este vital pentru noi să fim susținuți de cititorii noștri.

Dacă ne susții cu o sumă mică pe lună sau prin redirecționarea a 3.5% din impozitul tău pe venit, noi vom putea să-ți oferim în continuare jurnalism independent, onest, care merge în profunzime, să ne continuăm lupta contra corupției, plagiatelor, dezinformării, poluării, să facem reportaje imersive despre România reală și să scriem despre oamenii care o transformă în bine. Să dăm zgomotul la o parte și să-ți arătăm ce merită cu adevărat știut din ce se întâmplă în jur.

Ne poți ajuta chiar acum. Orice sumă contează, dar faptul că devii și rămâi abonat PressOne face toată diferența. Poți folosi direct caseta de mai jos sau accesa pagina Susține pentru alte modalități în care ne poți sprijini.

Vrei să ne ajuți? Orice sumă contează.

Share this